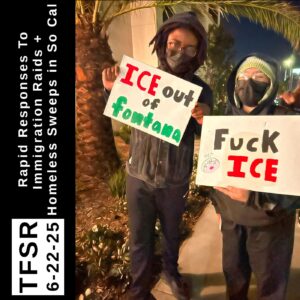

This week on the show we feature an interview with two anarchists activists in southern California about the recent resistance to Federal-led immigration raids in Los Angeles and the wider region. Both guests speak about their experiences working in rapid response structures to immigration raids, to anti-homeless sweeps and other community needs over the years and how they’ve changed as conditions and technologies have changed. We talk about inviting and engaging new activists and some strategies that showed success.

Some great writings from the streets can be found at Ediciones Ineditas: https://ineditas.noblogs.org/post/2025/06/18/fuck-i-c-e-city-wide-los-angeles-goes-up/

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Bella Ciao by La Plebe from Brazo En Brazo

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: Would you introduce yourselves with any names, pronouns, location information, affiliations, or other info that you want to share for this chat?

Ben: Sure, my name is Ben. I use he and him. I’m based in the Inland Empire, which is about an hour and beyond east of LA in Southern California. My day job is at a nonprofit organization that works in immigrant rights. I do mostly the legal side of things, but I’ve been an organizer for probably 25 years now, something like that, mostly on immigrant rights, but I have been active on many other issues as well. That’s pretty much me.

Anon: I’m Anonymous, I’ve been doing activism in the greater Los Angeles area for some years now. I’ve been involved in rapid response work and in a lot of mutual aid work as well. And I guess I’ll keep it at that.

TFSR: Well, the next question is about getting a little more detailed into the sort of work that you do, but you can obviously answer as you want to. Anon, are you doing rapid response around similar communities, or do you want to name the communities that you’re working around?

Anon: We have some folks that consolidated around SoCal in general, and this is how Ben and I became associated – through a number of folks who have been mobilizing around issues such as immigrants rights, but also such as responding to homeless sweeps, including a major sweep that happened a few months ago that we rallied a lot of people around. I guess in January, we had folks that really became concerned about how bad it was going to get. Obviously, we were right. So immigrants’ rights were the main issue, but we were also like, “Hey, they’re coming after people.” And they’ve been coming after people regardless of whether we’re talking to the Trump administration or anybody else. Obama still has the record for deportations, and then the situation with homeless sleeps in California in particular, I mean, all over the country, but this is an inflection point. So there were a lot of folks who were like, “Hey, rapid response around immigration stuff is the most important thing. But what if we also got a network of people together on a broad spectrum to show up and try to make life a little bit easier for the people most impacted.

Ben: It’s really, I think, a similar skill set. Rapid response for the sweeps that they do against our unhoused community, the immigration raids that have been going on like crazy, especially the last week or so. But also, when there’s fascist attacks or with emergencies, with the fires that you were talking about earlier, that’s the thing that requires a rapid response, especially when we can’t or refuse to depend on the government.

Anon: To go off of that, that definitely played a role. We had huge groups of people come together to start mobilizing goods around the city. This happens here, this is happening all over the country, all over the world, when disasters happen. A lot of those networks never went away. We had folks that were like, “Hey, why don’t we re-purpose this group from that effort we had to this new effort?” And that’s been helpful.

Ben: As far as I go, like I said, my day job is doing the immigrant rights stuff. The organization I work with has had a long-standing commitment to the people who are detained in the Adelanto Detention Center. And so I’ve taken on doing that work of visitation, the bond hearings, and the removal defense, especially for people that are locked up and asylum seekers. But I’ve also been doing rapid response since forever, pretty much responding to reports of immigration, filming those, documenting those, doing intake, interviewing the families affected or witnesses, trying to get them the resources they need, whether it’s legal resources or the stuff that you need because your main breadwinner has been picked up. That’s also one of the ways where there’s been that interface because immigrant rights folks have been doing this for a long time, and so we were able to transfer some of that to the people that are coming new on the scene, and learning about the rapid response, what it is, how it works, what doesn’t work, that sort of thing. And also activism, throwing down in the streets and organizing and doing what we can to keep people safe while we’re out there.

TFSR: I can see a lot of Venn diagram overlaps between all these types of engagement, whether it be showing up because the police are messing with a crowd of people or because of an immigration raid, as you said, or connections between the mutual aid stuff that was going on in 2020 because of COVID. Then, this would have preexisted the COVID pandemic, but the community mobilizations to provide food or transportation for families that were worried about immigration raids, at the grocery stores, at workplaces, at people’s schools, or whatever, or rapidly responding to reports of fash showing up in the street. That’s super interesting and useful to point to those connections. There are overlapping Venn diagrams between houseless communities and undocumented folks; there are going to be people who are in both of those camps, so to speak. Could folks talk a little bit about both of issues? The California context is a little bit different than other places in its official stances around participation in, as far as I understand, or maybe it’s city by city, but working with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The way that Trump talks about it, California is this place that’s absolutely overrun on the streets by people sleeping out, sleeping rough, or whatever all the time, and then also that it’s a bastion of a lack of enforcement around immigration laws or harassment of potentially undocumented folks by law enforcement. How would you respond to that supposition?

Anon: I can speak to that to start if you don’t mind, Ben. I wanted to jump in because I work a lot with unhoused communities, and I think it’s important to start with the United States and California on its own. Law enforcement is set up in this very patchwork system, and California, in general, is a “sanctuary state,” but each law enforcement agency has a different approach to how they deal with unhoused people and how they deal with undocumented people. I think that you see even those ones that are very “Oh, we have a policy.” The LAPD has a policy against being involved, but we’ve caught them numerous times having some involvement, and then they’ll backtrack and be like, “Okay, we weren’t really involved; this isn’t really what we were doing.” But then there are other agencies that are pretty much openly collaborating. I’ve seen that in some of the work that I’ve done in some of the unincorporated Los Angeles County.

It’s interesting because it felt, at first, like unhoused folks seemed somewhat inoculated from these raids because they were targeting people at their jobs. They were targeting people showing up at the obvious places that you would expect if they were profiling people. Home Depot, places like that, street corners. And then I did definitely see people who were like, “Hey, we want information. We want infographics.” And then more recently, what I’ve started seeing is–and I can’t speak to confirmations, but I can speak to some of the rapid response networks who have pointed things out and some of the unhoused residents that I work with that have pointed things out. I have at least one report of potentially ICE showing up and tailing a homeless sweep and using that as an opportunity to sweep people up. I know that there’s at least one confirmed report of an unhoused resident in Bell getting abducted by ICE. First of all, I’m noticing a lot fewer people when I’m doing outreach coming up, particularly a lot fewer people who don’t speak very good English coming up. So I have various communities who speak primarily other languages, and I’m seeing less of them lately, and I’m hearing from people who know and care about them that they’re deeper in the wilderness areas that they inhabit. I just saw a community that was fairly frazzled because they live in an unhoused encampment next to a Home Depot, and they’re telling me reports of “Hey, two days ago, 30 people were taken at a raid, and two of them were our friends and, we really want to get that information out there.” And a lot of the people that are like, “Hey, we want Know Your Rights materials,” are not the people you would expect. A lot of them are very much people who you don’t know where they stand politically, but they care about their community, and they don’t want to see them getting abducted.

Ben: It’s interesting. There’s definitely an overlap. Those videos have been surfacing the last couple of days of ICE out at encampments and picking up some of the low-hanging fruit that’s out there because they’re vulnerable. They’re exposed. They’re out there. And in some ways, undocumented people have more protections in a state like California than unhoused people do. I spent 10 years doing tenants’ rights, informing tenants of their rights, and we always would start with how there’s no constitutional right to housing, either in the US Constitution or the California Constitution, or any of the state laws or anything like that. If you get into a place, then you have some rights under your lease, and then there’s habitability laws and stuff like that, but there’s no right to housing. And that’s even gotten worse with the Grants Pass ruling, and it opens the door for abuse to unhoused communities. I can give a whole lecture on Know Your Rights. What are your rights as an immigrant at your home, your workplace, out on the street, in a vehicle, whatever. But what are your rights as an unhoused person? That’s a very short lecture. We still have the First Amendment, I guess. And the tolerance, too. The folks in the community, there’s a lot more pro-immigrant sentiment than there is any sympathy or love for our unhoused sisters and brothers, which is really sad. In some ways, it’s created a lot of protection for the people who are here who don’t have any immigration status. But it’s interesting to see that there’s that difference. In some ways, that overlap, and the big overlap is the poverty, even more so than the racial issues. But despite that, the communities or activist groups respond differently, and the community responds differently to unhoused persons living on the street or in crisis versus the crisis that’s going on right now in our undocumented or semi-documented community.

Anon: I definitely agree on the right side of things. I actually spend a decent amount of time putting together materials and helping educate unhoused communities on their rights. I meet people also at the intersection of–-and let me be clear, at least half of unhoused folks do not use substances, but I mainly work with people at the intersection of substance use and homelessness. I spend a lot of time handing people materials to keep themselves safe and alive and healthy and also educating them on like, “Hey, the stuff that I’m giving you, you’re legally allowed to possess,” because they do have those rights in California. The same goes for giving them materials on how to deal with sweeps. That said, right now we’re seeing people who will assert their rights and still get abducted, will assert their rights and have their window broken, and they’ll be pulled out of their car, they’ll have ICE break in their house. This is newer to that community, whereas the unhoused community, I don’t know how many lawsuits have been won reaffirming that unhoused people’s property is not to be taken, and they continue doing it anyways, both at a federal and a state level. And the same with the paraphernalia. They are legally allowed to possess paraphernalia that we give them because we’re giving it to them for public health and safety reasons, and yet, they’ll get ticketed and arrested for possession of pipes and needles and things of that nature.

Ben: Coming back to the question of the sanctuary and the way that it plays out in different areas or different communities, we have the state law that is really clear about setting those limits that local law enforcement can collaborate with federal immigration enforcement. But that doesn’t mean that the local police departments have the same level of tolerance for, say, day laborers who are looking for work out on the streets, outside of the Home Depot, or at other informal hiring sites or street vendors. Even though we have had now a series of laws to decriminalize street vending and to bring the food retail code up to date to allow for more access to people, to people who make their livings doing sidewalk vending, street vending, that sort of thing. But the cities aren’t necessarily providing those business licenses or making it easier. They’re doing some of them require million-dollar insurance policies and putting up those barriers. Why? Because they don’t want to see street vendors on their streets. Or they’re very restrictive about where they’re allowed to do that business, even though under the law they’re not supposed to have unreasonable restrictions. And I think it’s similar when it comes to the encampments. There are some cities that look the other way. They give up, like, “We’re going to be one of those cities where people can live unsheltered.” And then maybe that has a benefit to the city, in the sense that nonprofits, resources come in and get centralized there, and there’s a benefit to the general community because of that. But most of these affluent cities basically go police state, and they see unhoused folks walking in or driving in; they have laws against parking on the street, especially parking overnight, the anti-poor laws. And then there are the cities that are maybe either too big or break, and they say, “Okay, we’ll allow this type of activity in this part of town, on this side of the tracks, but we’re going to keep the white areas, or the rich areas, white and rich.” And they use the police to do that.

TFSR: I was gonna get to Newsom a little bit later on with some of the changes, and I do wanna talk about the political rifts that occur between him and Trump or the different administrations. My understanding is that last year, Newsom was spearheading this initiative to at least reward cities for running sweeps, and if not–I’m not sure if he was going to be punishing in the way that cities will punish people, like they’ll punish property owners or neighborhoods or whatever if there’s graffiti present that doesn’t get cleaned up. It reminded me of the human version of what Newsom was doing, like threatening punishment or at least rewarding cities for undermining houseless communities. Is that a fair description of the changes over the last couple of years with that?

Anon: I think so. I think that’s pretty fair. I think there was some degree where he was vaguely threatening, but ultimately, it was more of like, “Yeah, we’re gonna reward cities that follow through on this and maybe also potentially punish them by not giving them funding.” But he’s gone back and forth, and I’m not up to date with the latest thing. I’m trying to remember that there was something more recently that he had done and said. But, overall, he was actively lobbying for the Grants Pass ruling well before the Grants Pass ruling happened. Also it’s important to note that Gavin Newsom has been buddying up with a lot of far-right individuals lately, going on podcasts with Charlie Kirk and Steve Bannon. So it’s unsurprising that he’s listening to these voices. It’s unsurprising that he’s moving in that direction. I’ve looked at some of the legislation that he has put together since he’s been governor, and it’s interesting that the first piece of homelessness legislation he did was related to getting more shelters built and things of that nature. And it almost feels like he got jaded by the fact that it wasn’t happening on the timeline that he wanted. So then he decided, well if that’s not going to work, I’m going to start punishing people. He’s been one of the standard bearers for punitive action against unhoused communities for their very existence.

TFSR: How has immigrant solidarity work been shifting in the last couple of months, and in particular, a couple of weeks, with shifts in the federal approach? I wonder if you could talk about changes in the federal approach towards “immigration enforcement.”

Ben: There’s a playbook Stephen Miller wrote part of Project 2025… He’s a lawyer, and he’s studied immigration, and he had everything pretty much planned out about what the changes he wanted to make were, and a lot of those were implemented the last time. So, a lot of the changes have been things that they can do without going through Congress, through executive order, and through the way that the current immigration laws that are already on the books are applied or are enforced. So it’s been almost every day, especially the first month or so, multiple executive orders, decrees, that sort of thing, making life a lot more difficult for undocumented people. So that’s on one side, these are the laws, and these are what people are expected to comply with. And then on the other side is what is actual immigration enforcement? Actually, I don’t really like to use that term because it puts people in the mindset of “the law must be enforced.” I like to phrase it as repression because, really, that’s what it is. But so, what does the repression actually look like? And it’s people with guns going out and taking people. We saw it even before the inauguration, with this large-scale Border Patrol raid up in Kern County up at the Bakersfield area when Bakersfield is nowhere near the border. But they were considering the coast a border. I think that was a little bit of a preview of what was to come because they were going to the day labor hiring sites outside of Home Depot. They were going into the fields, the agricultural fields, and racially profiling people, and then basically rounding people up and taking them down to El Centro and detaining them there, and pressuring a lot of them into signing their own “voluntary departure” paperwork, and kicking people right out. Some people fought it and are still fighting it, and there’s an ACLU lawsuit about that. And that’s the thing that we used to see back in 2008, especially out in our area and before. Border Patrol uses race or the economic profile of a worker to stop people, sometimes even using force, pressuring them to sign their rights away and detaining people. And that’s part of what the purpose of detention is, too. They use detention, especially the threat of prolonged detention, as a way to intimidate people and pressure them into signing their rights away. Sometimes, they violate people’s rights without caring about what the laws actually say or what the rights are, and sometimes, they’re a little bit more careful. So I don’t know. It’s been very, very aggressive. It’s been escalatory.

I think the approach shows that Trump cares more about confrontation, about stoking a response from “liberal California” that he cares about deporting people because if he really cared about deporting people, he could deport a lot of people the way that Obama did, which was silently and with a smile on his face, whereas by using these very aggressive tactics, people are coming out on the streets in a way that they didn’t, when it was these behind the scenes, 287(g) agreements between local sheriff’s departments all over the country and ICE. Of course, California fought back against that and created the sanctuary law at the beginning of the Trump era, not during Obama’s time, but in some ways, this tactic, this very hyper-aggressive, macho, masculine, I-got-something-to-prove thing has provoked a response, which is beautiful because people have come out in big numbers. They’ve been very militant. They have not been hesitant to take over streets, to block entrances and exits of buildings, to prevent ICE from taking people out of workplaces. They’ve been very, very vigilant, sometimes a little too vigilant, reporting to the rapid response lines. And I think everybody’s organization that does anything to do with immigrants is overwhelmed with people saying, “What can I do? Can I take people groceries? Can I come volunteer? Can I translate, document, whatever it is? Can I be a Rapid Response Volunteer?” We don’t really know what to do with all these people because we don’t have time to vet them, train them, and supervise them. We’re working on it, but it’s been really beautiful to see, and I hope we can turn it into something longer-term. Because this happened last time, and we had Indivisible people coming out, and they were doing some of the same things. But then, once Biden got elected, they all went home. So that’s where we need real political education, pulling out the real values that are drawing people into the streets right now, the values of solidarity and of racial justice and of having a heart and help taking people along. There are big differences between the first outbursts of immigrant rights enthusiasm and the community coming out for the trans people who were under attack at the beginning to No Kings. So there’s room for a dialog or holding people’s hands taking them along and saying, “Hey, you might be at the beginning of your political journey, but we have a long way to go.”

Anon: Yeah, and that’s where I think we have evolved quite a bit in the last several years. For one, we made a huge effort with the rapid response to help people with the fires. That culminated in some of the first examples of seeing massive numbers of people coordinating. And it was very unruly and, in many ways, disorganized. And it led to a lot of transporting of goods from one location back to the other location. People were just like, “I want to get something done.” And it was at some point you’re digging a hole and then refilling it, and that’s the work, and they’re doing that on loop, on end. Then we started learning how to build networks, from the time of the fires and that already had a massive number of people in them. And then, in other cases, it was like, “All right, here’s an existing Rapid Response Network. And this thread from this Rapid Response Network populated from 50 people to 800-900-1000 people.” And everyone’s in the chat asking how they can help. And it was like, “Here’s quick educational stuff, and here’s another local thread for you, or here’s a thread on a specific topic like dealing with hotels.” It’s not perfect, but I feel like that has been a beautiful part of this whole process. There’s still a lot of things that I’m seeing on the ground. What’s been wild is, I was listening to It Could Happen Here, and James Stout was talking about the people who are showing up, and he’s like, “There’s a ton of high school children of immigrants who were out there for the first time.” And I’m like, “Well, we had some kids out there in other past movements, too.” And then, seeing it on the ground, you’re like, “No, no, no, really.” It’s both beautiful and scary because you’re seeing these 15-year-old kids who are out there with no face covering and nothing to protect them from riot munitions who are putting themselves out there and putting themselves in harm’s way. So it’s not perfect. We still have people that are not getting connected with the right groups. And naturally, what happens then is people don’t get connected with groups at all, or people get connected with Rev-Com (formerly RCP), or PSL (Party for Socialism and Liberation), or some other group that might lead them to in a direction they wouldn’t want to go in. No shade on some groups, definitely some local chapters of certain groups can be okay, but generally speaking, I found those groups tend to lead people astray. And we want to see people showing up and making sure they have the right protective gear on, showing up and making sure that they know how to effectively protect themselves digitally. And I think we’re starting to see the beginnings of that.

The other side of things is communicating our message properly. So one of the issues that’s been happening right now is we have folks showing up the other day to deal with a situation at Dodger Stadium. We had ICE showing up at Dodger Stadium. And the Dodgers have been doing a pretty miraculous, marvelous job of propaganda, and they’ve been doing that for their entire existence. The Dodgers‘ stadium is built in a brown community. They displaced the people of Chavez Ravine, and it’s been one thing after another of displacement and harm to these communities ever since. Still they have a massive following of folks from brown communities because they’ve got a great PR operation going. And the thing they did immediately when they got called out for having ICE there was, “Oh, we turned them away.” And even Democracy Now ran with that narrative, and there’s a lot more to that story. I’ll start with that. We know for a fact, because we have picture and video evidence, that they’ve been coordinating and showing up to Dodger Stadium property all week, and we have no effective mechanism to combat that. We can come on shows like this, but when MSNBC, CNN, and even Democracy Now are running with the narrative that the Dodgers ran them out immediately, then what happens is you have 30 people show up to the protest rather than 300. And there’s not really a good way to effectively combat that yet.

TFSR: With the changes at the federal level, with enforcement around attempting to immediately deport people rather than focusing on putting them through a legal process that you can intervene with to try to bail people out or get them a lawyer or whatever. How has rapid response shifted with that, and also with the shift around DACA?

Ben: That was a really big change that Trump tried to make the first time around and was challenged, and it was halted. This time, it’s been moving forward since pretty much day one of the administration. There’s always been expedited removal on the books, but it used to be if you were within 100 miles of the border and had been or were suspected to have been in the country for less than two weeks, they could expel you summarily, without any due process, without any chance to go before a judge. Now it’s not near the border, it’s anywhere in the country. And now it’s not two weeks, it’s two years. So a part of that has been the preventive side of things, in terms of the Know Your Rights, and try and encourage people to know what that policy is. Like if you’ve been here for less than two years, or for more than two years, then to have somebody to prove it, or be sure to express it, if you’re getting taken in. Or if you’re afraid of returning, then definitely shout that from the rooftops because the ICE and CBP, Customs and Border Protection, it’s no longer incumbent on them to ask. You have to be the one that says it. So with the rights violations, with them taking people without probable cause, without warrants, without any proof or reasonable suspicion of the person is from somewhere else or doesn’t have status, it’s been really important to try to get in and do an intake interview as soon as possible, even before there’s a bond hearing, because sometimes, to get bond, you have to file documents that show identity and stuff that, and so you could be handing over evidence that the government didn’t have in the first place, whereas, if the person had that their rights violated, and they stood up for their rights and had them violated anyways, then there’s potential for a motion to suppress, motion to terminate, get that person out of removal proceedings entirely, rather than try to fight for them to have bond and fight a deportation case.

Not everybody, even immigration attorneys, always know all that stuff. It’s not really that common to make motions to suppress because the evidence being gathered was the fruit of the forbidden tree. And with a two-year thing with the people with expedited proceedings, that’s tough because you’re not even in court. So you’ve got to try to find some way while the person is still detained before they’re expelled from the country that they’ve been here for two years at least. Sometimes you can do that with pay stubs or leases or whatever, or try to help that person assert their fear of return and maybe support them through if they make fear of return claim, they’re supposed to have a credible fear interview, and if they have any legal support in that, then that’s only going to benefit them. So it’s been a struggle to get the legal support, the legal resources up into Adelanto or in the Metropolitan Detention Center, or it’s sometimes even harder to get people down to the border and on those calls or video calls or in the detention centers to provide that information, especially when they act very quickly. They also had been transferring people around like crazy. Yesterday, I visited a guy who had been in seven different centers; he was picked up in, I think, Connecticut and had been in seven different facilities before he got to Adelanto, and now he’s been in Adelanto for two months. They’ve been picking up people here and sending them to Texas, and meanwhile, they’re bringing people from Texas here. None of it makes any sense, but I think part of it is to distance people from their networks of support, their legal counsel, and their families that can provide resources and generate a lot of confusion. So that’s how I would say rapid response has shifted a little bit.

TFSR: Did you get a chance in there to talk about the differences in Adelanto?

Ben: Not really, no. We’ve been fighting against Adelanto before it even opened. I think now it’s in year 12, and unfortunately, we lost that fight. It’s open, but we’ve taken on that struggle in other ways. Everything from prayer vigils outside to having visitation programs so we can have eyes and ears on the conditions, through church groups and stuff, to litigation and community organizing, old-fashioned pressure campaigns, and we were this close to getting the ICE processing center shut down. It was under task order, and it was down to three people. And then one of them got deported, it was down to two people. And then right before the election or before the inauguration, the task order was lifted, and the new incoming administration said there’s not going to be any task order here. So it started filling up. Of course, GEO Group was a main contributor to the Trump campaign. Their stock prices doubled the day of the election, and they’re trying to cash in.

That particular facility went from something 300 people just a month ago, that was the end of April, and last week it was 1800 something, and now it’s at capacity. The capacity is at under 2000. There’s another facility right next door, Desert View Annex, which held about 700 or 730 people, something like that. Apparently, it’s also at capacity, which may be why they’re sending other people. Everybody came in so fast that the guards couldn’t handle it. They lost control. The detainees were the ones organizing the count because if there’s no count, then there’s no food, there’s no water, there’s no progress, and they don’t get out for yard time. But the guards didn’t have control, so they were jumping on tables and pointing their pepper ball guns at people ,yelling at them. People didn’t have enough clothes. They held only one change of clothes. They couldn’t wash it. So they’re washing their uniforms with shampoo in the showers. There wasn’t enough food, all the food was late. They started running out of water. I talked to one guy who was scared that because of so many people coming in at the same time and people being desperate, he was concerned that the tension was potentially creating very dangerous conditions. So it seems it’s calmed down a little bit, but they’re definitely still struggling, and that has created problems with family being able to visit, family being able to deposit money into their commissary accounts, or on their phone accounts. It has definitely been a big problem for attorneys and nonprofit legal workers to be able to get in, and the detainees have access to counsel. Huge issue.

Anon: Ben, I recall hearing something about the credible threat standards changing under the Biden administration and then the Trump administration taking advantage of that. With regards to how someone has to audibly say they’re in fear, do you know what I’m referring to?

Ben: Yeah. One, they’re not requiring the ICE or CBP to inquire, “Are you afraid to return?” before either detaining them or putting them into an expedited removal process. Two, I’ve talked to colleagues who have had clients in credible fear interviews, when they actually do do the credible fear, they’re not even really asking questions. It used to be probably a good hour to do one of these credible fear interviews because they’re done by asylum officers who are trained to get at the truth of the situation of the people that they’re interviewing and find out what their situation is and if they’re afraid to return. Now they’re taking less than 20 minutes because they’re not even really asking the questions.

TFSR: This last couple of weeks, there’s been turmoil in Southern California with federal troops and, in some cases, law enforcement aiding them, raiding facilities, raiding business places, raiding community spaces, and kidnapping people under the auspices of “immigration law.” We’ve seen communities fighting back in really amazing ways. This has been alluded to in some of the prior answers, and I’m sure that most of the audience has seen some of the videos. Is there any part of that, like federal intervention and community response, that you haven’t already referred to that you want to share?

Anon: I’ll jump in on this one. I’ll start with the stuff that has preceded everything. A lot of activist communities knew this was coming and I think a lot of people get caught up in the glorification of protest itself., and they lose track of the stuff that needs to happen between that. This is way we have these protest movements that burn hot and then fizzle out. I should say there’s also a distinction between a few different kinds of rapid response and I’d like to have Ben expand on what I’m about to say with this. There’s the legal side of rapid response, which is what groups like CHIRLA (Coalition for Human Rights of Los Angeles) do, for example. And then there’s the side of rapid response that you see from groups like in LA, we have, and I want to say that this is a national, or at least California-wide coalition. There’s a coalition called the Community Self-Defense Coalition that came out of a group that’s been doing this work for a long time called Union Del Barrio. They encourage pretty direct showing up and confronting ICE raids as they’re happening. In a lot of the cases, it’s like, “Hey, let’s get people to show up into communities at 5am and patrol the area and see if you can find some huddle of ICE officers and other federal officers showing up to disperse out to the community and start taking people.” That rapid response is what a lot of activists were like, “Hey, we want to get these networks going.” So I’ve definitely personally witnessed local law enforcement coordinating with federal law enforcement to do some of these raids in some of the communities that I’ve helped and I know a lot of the other people that have seen similar. Like I mentioned before, I don’t remember if we were recording it or not, but the LAPD is a little bit more coy about it because they do have pretty direct policies against doing that, so they’ll find ways to weasel word out of it, saying that they were collaborating. So that’s been going on for months now, and then it exploded. There was a specific event that led to a bunch of people getting very upset, and that led to the spontaneous protests breaking out.

Let’s bring it forward now and talk about what’s going on at the moment. People started showing up in the streets, and they were very upset. And it was, again, the children of immigrants and random Angelenos who were not happy about what was going on in their streets, who had never protested before, in many cases, who were showing up, and plenty of other seasoned activists as well. But it was definitely a huge mobilization of average Angelenos who are not happy at all about what’s going on. I’s also important to mention that these are not the biggest protests by any long stretch that Los Angeles has ever seen. Most protests, when there’s violence, the violence starts with, oftentimes, escalations from cops. And we had cops, in many cases, randomly shooting less lethal munitions at people and showing up and beating people with their clubs and such. And people responded by escalating themselves. You saw the display of people burning Waymos and throwing Lime scooters down at cop cars. And that all happened after the police escalated that. Let me be clear, when I’m talking about the police right now, the vast majority of that violence has been LAPD and LA Sheriff’s Department.

TFSR: When they’re not shooting at each other.

Anon: I was going to get to that in a second, actually, which was awesome. So the situation with the National Guard has been that they’ve deployed some munitions as well, but for the most part, they’re standing in standing in front of federal buildings. And the Marines have done even less, they’ve arrested one person for a very brief period of time. The vast majority of the violence has been done by police. The LAPD and LASD have a long history of brutality, both in terms of protests and in terms of the community in general. That’s not to say that other law enforcement doesn’t, but definitely, LAPD and LASD are pretty notorious for it. They were all out there, as was CHP, and we saw that going on. Let’s not let the narrative get out there about the importance of the National Guard and other federal troops. It’s been primarily LAPD, LASD, and then a little bit of CHP brutalizing people, and then a little bit of assistance from these federal troops, which mainly means they’re wasting federal tax dollars and sending them out here for no reason. Because, as Gavin Newsom and Karen Bass will definitely point out, they can send LAPD LASD and CHP to brutalize protesters on their own; they’re more than capable of doing so. When you mentioned the law enforcement shooting each other, it was no surprise to me because that was a crowd that was packed in like sardines right by City Hall doing basically nothing, and cops started wantonly opening fire on the crowd. So, it was completely unsurprising to me that LASD managed to hit a bunch of LAPD officers in the process. That was quite fun to witness.

Ben: Following up on my comment about how sending in the National Guard was for the purposes of confrontation, I also feel there was an element of distraction there because when the community finds out the National Guard is coming, then people want to protest that. They look at that in itself as an abuse, and it is. So everybody rushes downtown to where the National Guard is to protest. And things escalate and whatnot. Meanwhile, we forget about what we were protesting in the first place, which was ICE and all these other federal agencies that they’ve deputized, stealing people out of the community. That particular day, I think it was Saturday, I think was the 14th, when there was a big mobilization against the National Guard, that was the day they started hitting the car washes, and they were picking up sidewalk vendors over on the west side, and they were very active out here in the Inland. I think sometimes it’s easier to respond, and that’s where the interest is, the fetishization that was mentioned earlier. But one of my comments was, wouldn’t it be a shame if they threw a riot and nobody came? It’s not always the most strategic thing to rush into combat against a very well-armed and militarily trained opposition force. Hopefully, one of the takeaways is how we have larger-scale coordination? How do we have larger-scale discussion strategies? Because I think that’s really the only way that we’re going to be able to really do things like strikes, boycotts. They want to go after people in the fields? Well, the food is going to rot. They want to go after people in the warehouses? Well, those warehouse goods are not going to be moving. And that’s going to affect the bosses. They’re the ones that the Trump and all of them are listening to anyways. The tariffs got dropped the day after he had a meeting with Walmart and Lowe’s and whoever else CEO. The other thing is that I don’t think that, the National Guard, people were worried about them, but those are Californians, they come from our community. They’re working-class people who were looking for a way to get into college or a job, and they do not want to be aiming their guns at us. I saw a great video of, I think, it was a former veteran yelling that at them, like “We’re you, you guys are us,” and encouraging them to think and to feel and to recognize what they were doing, where their alliances are or should be. The Marines, too. The Marines don’t have the best reputation, but they’re not the people who want to get deployed against Americans. How much of the rhetoric do they believe that we’re all Californian illegal terrorists and stuff? I don’t know. I’m not really clued into that community. But I don’t think we should give up on the people that are in those forces. I’m not a fan of cops, obviously, but when it comes to National Guard, army-type people, I think we have to organize on every front that we can.

Anon: I want to add to the beginning of that. I may have a little bit of a different take on troops, but I’ll leave that aside. I think that the Trump administration came into the whole thing of them sending ICE to California knowing that this would happen, knowing that it’s summertime, and this is when protests happen, and this would be a great opportunity to cause people to show up in the streets, and use it as an opportunity to repress people and try to rally his base around the idea of normalizing that repression and normalizing more vehicular attacks at protests. You’re starting to see people talk about coming and doing violence at protests. I think that there’s definitely a part of his playbook that comes down to “I want protests to happen because I want people to show up so that my followers can attack them, and I can attack them as well.” I really do think that protests are an important component of all this. And I think Ben surely agrees with that. I think, though, that we both agree that protest is probably best used as an opportunity to get people in when they’re agitated and onboard them into largely more meaningful things, as we’ve been talking about rapid response networks, mutual aid work. These are all the things that build the infrastructure for us to make lasting changes in our communities. Sustainable movements come from people engaging in things that are not putting them constantly at risk of arrest and injury. That’s really important that we’re starting to find more and more ways to get people who are on the ground doing that to see that fact. I’m seeing a lot of those people that are showing up in the streets mad, funneling themselves into rapid response networks right now, these very informal, unvetted ones, and then we’re like, “Hey, by the way, if you want to get closer with people who are really, really doing this work, here’s a training that you can go to.” So I think that we’re seeing the beginnings of some of that stuff. I think that’s really important. And I definitely think that him deploying the National Guard and him deploying the troops was absolutely more a tactic to get more people on the streets and give them an opportunity to show the reasons why he needs to repress people.

TFSR: Some immigrant solidarity organizations have been focusing on Know Your Rights trainings to prepare for raids and for door knocks and stuff. One interesting approach that I’ve been seeing, Siembra in the triangle in North Carolina has been doing, among many other groups, has been to focus on places of employment with the training of employers who may be invested either socially, personally, politically, or definitely economically in their workers. Are you familiar with how this approach has been working, considering the shift in the way that raids are being conducted, and what secondary outcomes are raised by this? Are employers and their class getting a little more invested, maybe in the workers that they rely on to make all their money?

Ben: Well, I think the employing class has always basically been pro-immigrant and even pro-immigration reform. The last time there was actually a reform bill that came close to passing, the BizFed and the Chamber of Commerce were all for it. It was a block of Congress members, mostly in the Midwest, in predominantly white districts, that didn’t say they were proposing it for racial reasons, but it was very clearly a racial issue. So I don’t think that’s new. It has been interesting to see the way that some employers have actually stepped up and defended their workers. I can’t say that it’s because it’s anything that I or the organizations that I am aware of have done to reach out to them and train them. When we’ve done workplace KYR, workplace or worker-oriented trainings, it’s been about worker solidarity and in collaboration with unions or non-unionized workers, and not so much with the employers, because the employers don’t really like us also telling them about worker rights. But I have seen it, and I’ve talked to warehouse workers who were at work when their boss said, “Hey, the migras are outside, so we’re locking the door, and we’re telling them to go away, and you guys sit tight, and we’re going to pay for the day, and as soon as it’s safe to go, you guys can go, but go out the back door, carpool,” that sort of thing. So that was really cool and interesting to see. But it’s not coming out of the movement. It’s not coming out of a vision of justice or migrant justice. I think it’s coming out of more of self-interest and right now, being the cool boss, so that I can keep my workers, and they’re going to have a debt of gratitude to me or whatever, and not unionize or not demand a fair wage and that sort of thing. That’s my take on it.

Anon: I was going to mention the cynical side of it. I was watching some local news, and they were actually showing some video from a raid, and it was wild to see them talking to this boss, and he’s been talking about how he’s shocked that so many people lied to him on their applications and now he’s gonna have to replace his entire workforce. And I’m like, “Hmm, so they all lied to you about the facts of their immigration status, and you hired all of them? I guess you’re really quite the dupe here, huh?” “I’m shocked that I have all these immigrants working for me!” There’s definitely a cynical side to all that. That is all I’m pointing out.

Ben: There’s also the predatory side, which is something that has been coming out about the Ambiance Apparel raid that happened. It was that same day, the 12th or the 13th, where the workers, once they’re getting processed in and whatnot, they’re being told that their boss was under investigation for money laundering, so their suspicion is that the boss reached some deal with federal law enforcement that he would sell out his workers, let them take the workers, and he would get some deal of non-prosecution or reduce charges, or something like that, for whatever he was really under investigation for. You’ve seen that before, where they’re supposedly investigating the employer, even for something like I-9 violations, or hiring workers without status, and the workers are the ones that get taken, and nothing happens to the boss.

Anon: I know CBP and DHS, in various cases, have been caught actually collaborating in those things in the past.

TFSR: I really appreciate the time that you’ve taken to have this conversation. You’ve pointed to some lessons about trying to not focus necessarily on the glamorous, maybe in some cases, macho elements of the protest, trying to use the opportunity of people being riled up to get them trained up, to keep them from making basic mistakes, but try to get them to think deeper about the involvement and what resistance needs to look like to make effective change. These are things I got out of some of the stuff that you said. I wonder if there are any other lessons that you want to point to in these last couple of minutes from the–I will say–spectacular, but also really impressive resistance that was seen in streets around Southern California recently.

Anon: Thank you. I want to definitely add one more thing. There’s also the way that you go about protests. One of the most effective things that we saw during this was people going after hotels. There were hotels where ICE was being housed, and a lot of these hotels knew that ICE was coming or that ICE was there and didn’t seem to care until the community came out and were like, “Hey, we’re not okay with this.” In many cases, we effectively got them to kick ICE out of the hotels. It was interesting, too, because it was effective, but then there were also several of those protests that weren’t very effective for a variety of reasons. And then you saw autonomous community members coming forward and giving these written down critiques to those groups of people like “Here are some of the tactics that have been more effective.” There’s specific communities where they really force sound ordinances past 10pm, and they were in particular, this one process was it starts at 9pm. They’re like, “Hey, let’s bring these noise-makers. And let’s do this, let’s make sound.” On the first night of it, they did that, and then they really cracked down on the noises. There’s some degree where there are clearly some people who are new and a little bit scared, so they actually listen to the cops rather than defying them. Then there’s the other side of it, where it’s was because of the fact that they listened, they ended up all right, we’re gonna go ahead and do this acapella, and it became a little less effective. Fewer people were showing up at the night ones. Also, you’re not showing up when people are outside and can see, and you can talk to people at the hotel about what’s going on. And so they gave that critique, and they’re like, “Well, these other protests have been effective because of this, or this particular protest that you changed that strategy,” and then that ended up working. It was really cool to see this, pretty much in real-time, critique of that, and to some extent, people listening to that and using new tactics to good effect.

Ben: I agree that the hotels is an example of creativity and agility. If our movements want to be successful, we definitely have to be creative and agile. Some of those hotel actions were also a lot of fun. And so, it helps us to bring joy into the movement and our actions, too. Another one that we should always remember is that the borders are made to benefit corporations and the oligarchs, and so the more transnational international solidarity we have, the better off we all are. And especially with the climate crisis, it affects all of us. And it’s not a new idea. It’s an old idea, but it’s really about labor. It’s about workers being protected and having access to the fruit of their labor. If the corporations could be multinational, then why can’t the worker organizations also, and they should be. And so it’s an old idea that maybe we need to bring back in.

TFSR: Well put. All right. Ben and Anon, thank you so much for having this conversation and for the time. I really appreciate it.

Anon: Thanks for having us.

Ben: Thanks. It’s been great.